Poems of Fierce Soul: Poems in Guaraní and in Spanish by Mario Castells/Juan Ignacio Cabrera

Mario Castells (Rosario, 1975) is an Argentinian-Paraguayan poet who leads a dual existence — between Argentina and Paraguay, and between the Spanish and Guaraní languages.

Playing between the pseudonyms and persona of Juan Ignacio Cabrera and Miguel Ángel Soler, he wrote the poetry collections Blood Attorney (Fiscal de Sangre) and Ayvu Pochy Ñe-endy (Poems of Fierce Soul) in Guaraní and in Spanish (three of the Poems of Fierce Soul — Lopi Clemente, Horror-filled Land and Icho Laku — are published here, in Arturo Desimone’s English translation. (Be sure to click on the poem’s titles to hear the poet reciting in the beautiful Guaraní language!)

Mario is a tireless, militant-marxist agitator for the cause of agrarian reform. “Nothing compromises my intellectual militancy’’ Mario likes to say. We better believe him. Born in 1970s Argentina to parents who were politically exiled from neighboring Paraguay during the Stroessner regime, the poet spent some of his formative years in rural Paraguay. He still constantly crosses the border. His novella El Mosto y la Queresa “The larvae and the ripening wine”, generational tale about Paraguayan immigrants in Rosario’s working-class suburb of Villa Diego, won Rosario’s 2012 municipal literary prize. His articles treat Paraguayan cultural dilemmas. A new generation of young Guaraní poets and writers are emboldened by Castells’ translations, cultural and literary criticism.

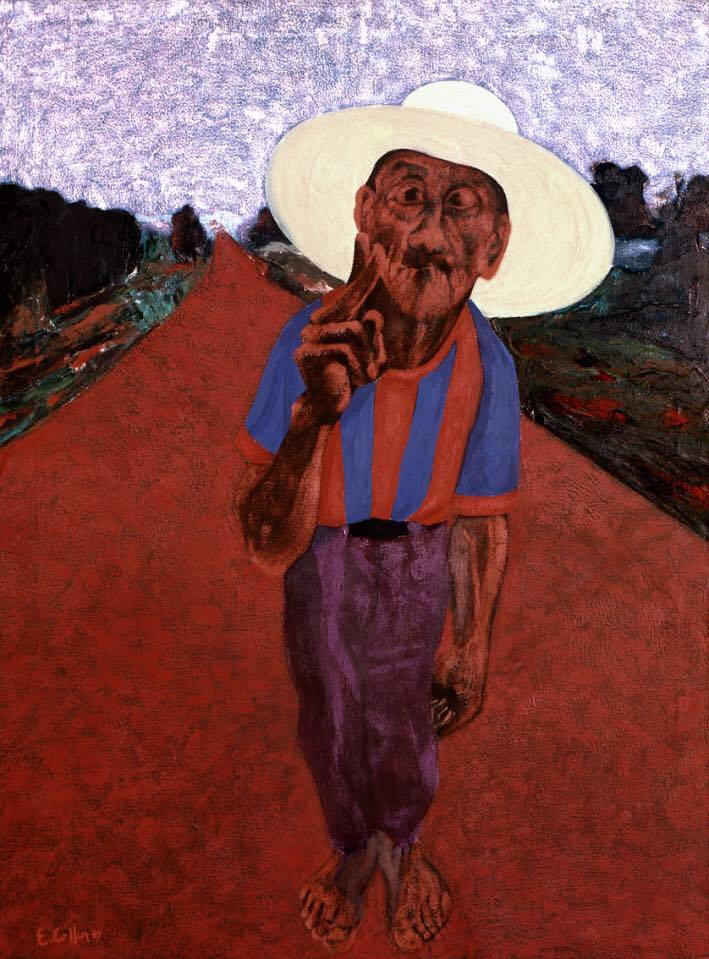

The poems by Mario Castells are in the company of these haunting images, courtesy of Paraguayan painter Enrique Collar, a friend of the poet and of the translator.

3 poems from Ayvu pochy ñe-endy / Poemas de Alma Feroz, “Poems of Fierce Soul” by Juan Ignacio Cabrera / Mario Castells

Translated into English by Arturo Desimone

Lopi Clemente

Uncle Clemente

(to uncle Nelson Ortíz)

The solitary cross rises in the woodland

once more, its thin scream.

It will be another afternoon of bad weather

Right over there stands Don Clemente:

saintly man who prays

uninterruptible estuary orations

to his loved god.

His oxen at rest

in the timber-shade

and I think they may have drunk

more water

than what is prudent.

Icho Laku

Inscription on the grave of María de la Cruz Cabrera

“Along the dark angles of their rooms lurks the pora-ghost…”

-ALEJANDRO GUANES

It is a closed-off night in the Neembucoo.

And, in effect, I see you

in the obscure calm

beneath the ruins

of my apartment decked in Saint Anthony’s winter…

You don’t walk, not enacting any bodily motion,

but I know

you are exhausted still.

You, the deceased, are neither my uncle nor my father

nor my grandfather

nor one of my newest dead.

Dead from the first planted rows of trees

in the pink of memory.

I revile that you bear a Cruz.

Silently risen on only one leg

emulate the swans on the Piraguasú lagoon.

I feel like an offshoot of myself…

as if I were carrier of your corpse upon my shoulders;

and even by throwing it at your ghost

still I fail to make your weight less.

I make myself shudder.

You did not recoil at fate.

You were an extraordinary soldier.

Mangled by the farm, yet you stayed on.

Those trembling creeks, lagoons and marshlands

count, in their names

the history of that massive misadventure

I wish we could have a conversation, that I may know your story.

This desire harasses me in dreams.

Perhaps an open-mouthed dream

Suspicious of the harness of the story-teller

Your opposite, as much as ours.

I cannot imagine your maimed returning to the valley, a paralytic,

survivor of only one single hillside-genocide.

Tigers, sickness, lobsters,

liberal forest militias, as recounted by aunt Maria

at the bonfire gathering,

they did not let you lift your head.

Many evil things, mi señor, they vandalized in vanity.

I need you to tell me

I, who am your progeny and your very same blood,

I need to locate your tremulous word.

The knowledge of how you ever managed to escape

the gruesome chasms of Tooyootee.

You are no longer in the world.

Rely, strongly on the tale,

on your eye-witness, my dear chief.

Use my throat, my heart.

Whatever you need to speak of this, faithfully, from inside me.

Horror-filled Land

To Martin Arzamendia.

“What will become of us? culture of evil has devastated us and in the coop of death’s barn we remain without identity.” -ZENÓN BOGADO ROLÓN

A mighty force

domesticates all that is overpowering in these valleys;

as cathedrals

the woods are razed and the corpses of the trees carried off

in whining trucks,

pacing at the gait of cancer,

of a counterlife.

In the world’s eyes

there is closure-heart, storm-ready,

there is impenetrable thorn-brush,

there are spines, disarray

How come? Why this fatal mandate

to make these ramshackle ranches, precarious farms endure

so many penuries?

The cedars soak and store up heaven, measure storm

and make cushions from the time-fabric,

education by bamboo-stick

Tell me

How come no one ever extinguishes that sadness?

How come no one ever senses heavy silence

as if it were a skirt made of plant foliage?

The church bells stammer

and it is the call of the lazy-bones christian god,

call out to his faithful-grateful

back to the fold, fuse together.

Dying birds, shriek out your last chirp!

Shriek, the anima souls, push out your scream, spirits!

You got my permission, consent granted. And along with that

you can have my passionate puke.

Translator’s note on Icho Laku: As I interrogated Mario Castells about the meanings of words and places in his poem Icho Laku, he warned me ‘’’be careful translating the word for ghost, “Porã is pretty, beautiful; póra is a ghost, in Guaraní, not to confuse two, they sound very different.” I had first translated porã for the lurking ghost as ‘’ the wandering beautiful one’’ but then corrected it to ‘’the wandering ghost,’’ after contemplating phantom for little while.

The title of the poem Icho Laku remains in Guaraní in Castell’s/Cabrera’s own Spanish version of poem.

Icho is an intimate, tender way of saying to those of the same blood “Sir, Don, or karai (an authority in Guaraní) and Laku is the Guaraní bastardization of the Spanish surname “La Cruz’’, a surname of Castells family and his pseudonym.

The subject of this poem, Icho Laku, is Castell’s (Juan Cabrera de la Cruz’s) ancestor, a great-grandfather, lone survivor of a family of 10 brothers after the “Guasu War,’’ (“The Great War”) of the Triple-Alliance — in which Argentina, the Brazilian empire and Uruguay joined forces to decimate and plunder Paraguay, which had been until then one of the most affluent and self-sufficient states in the region. Paraguay lost nine tenths of its male population in what was tantamount to genocide. “My great-grandfather was left a cripple, after the second battle of Tuyutí, according to some accounts, or it was in the ambush of Humaitá, according to others. He was a devotee in the order of the mystic Saint Anthony of Padua, and a cattle-rancher of the ranks of the Lopez army, ranking amongst the cavalry of Captain Bado, his friend and his relative.

“After the war, when Icho Laku returned to the town where both he and his wife Maria del Pilar-Segovia were from, he founded a chapel to Saint Anthony. Today, there is a parish there with a little church called Saint Anthony of Laurels, it is where my mother’s family is from. My great-grandfather was named José de la Cruz Cabrera — named after the same Cabrera who founded the city of Córdoba, descendant of the Bishop of Asunción until the end-time of the colony. Despite a distant patrician past, our family is not moneyed in the slightest: it is a family of small cattle-herds, of the rural middle class at most.” Castells has no intention of leaving the shadows cast by his fascinating ancestors. It seems that within the deep solitude in which he writes he is able to do justice to his longing to better understand them.

Mario Castells poems read as blood-chronicles, inhabited by his longed-for and loved ancestors, and by the unmerciful history and the great beauty of Paraguay. He is a warrior- poet with a haunted universe, and with a pure red politics that seems, at times, as wholly uncompromising as his aesthetics.

~

About the translator/blogger behind “Notes on a Return to the Ever-Dying Lands” for Drunken Boat:

Arturo Desimone, Arubian-Argentinian writer and visual artist, was born in 1984 on the island Aruba which he inhabited until the age of 22, when he emigrated to the Netherlands. He is currently based in Argentina (a country two of his ancestors left during the 1970s) while working on a long fiction project about childhoods, diasporas, islands and religion. Desimone’s articles, poetry and short fiction pieces have previously appeared in CounterPunch, Círculo de Poesía (Spanish) Acentos Review, New Orleans Review, DemocraciaAbierta, BIM Magazine, Knot-Lit. A play he wrote won a prize for young immigrant authors in Amsterdam in 2011, and published in the world-lit journal of University of Istanbul. His translations of poetry have appeared in the Blue Lyra Review and Adirondack Review.

Originally posted June 14, 2016 on https://medium.com/drunken-boat by Arturo Desimone.