Valerie Henitiuk

Valerie Henitiuk is a professor at MacEwan University, Canada, where she also serves as Executive Director, Centre for the Advancement of Faculty Excellence (CAFÉ) and University Advisor for Indigenous Initiatives. She previously served as Director of the British Centre for Literary Translation at the University of East Anglia, UK. Her books include Embodied Boundaries: Liminal Metaphor in Women-Authored Courtship Narratives (2007); One Step towards the Sun: Short Stories by Women from Orissa (2010, co-edited with S. Kar); Worlding Sei Shônagon: The Pillow Book in Translation (2012); and A Literature of Restitution: Critical Essays on W.G. Sebald (2013, co-edited with J. Baxter and B. Hutchinson); forthcoming is Spark of Light: Short Stories by Women Writers from Odisha(co-edited with S. Kar). Her work has appeared in Meta, TTR, and Comparative Literature Studies, as well as in Thinking through Translation with Metaphors (2010); Translating Women (2011); and A Companion to Translation Studies (2014). Since 2012, she has edited the journal Translation Studies. She was recently awarded funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) for a research project titled: “This too is a story. That is how its words go.” The Translation and Circulation of Inuit-Canadian Literature in English and French.

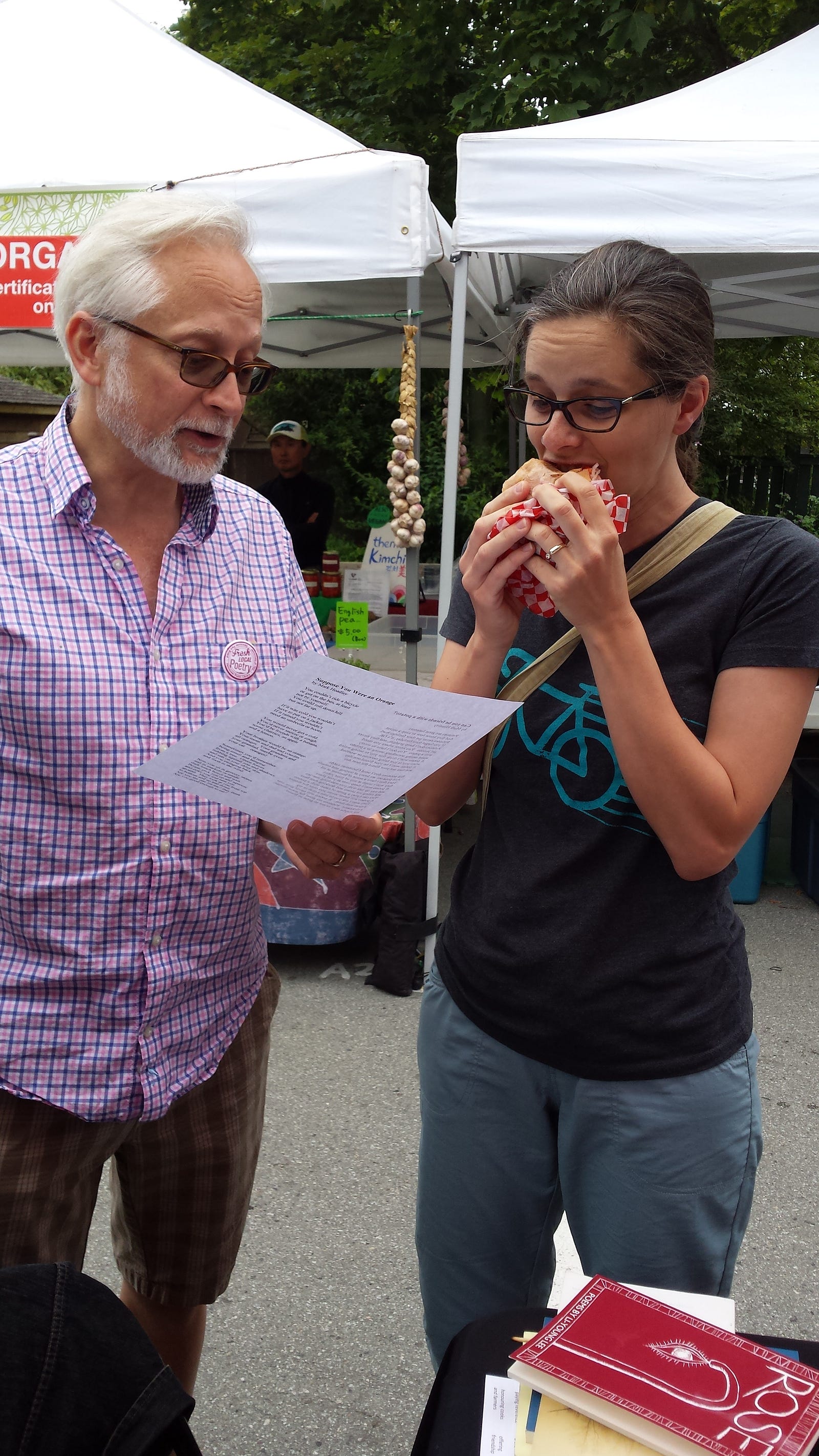

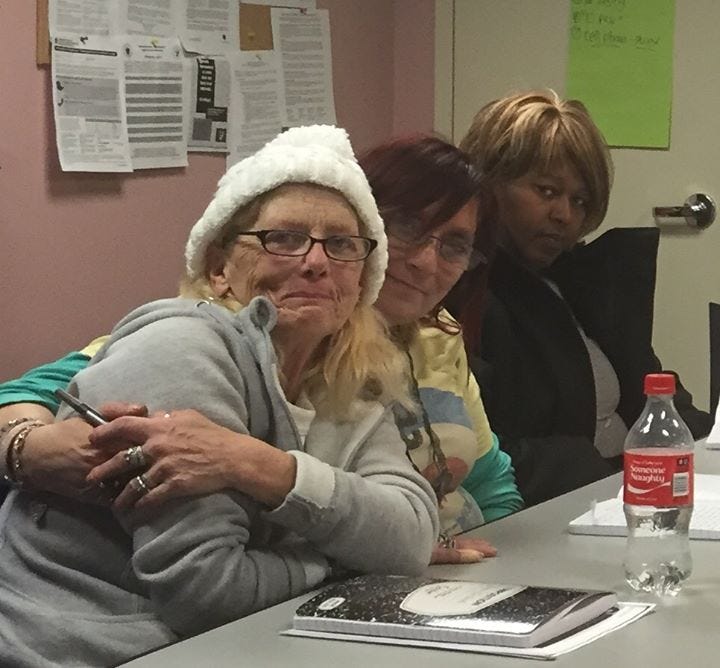

I first met Professor Henitiuk at the University of Massachusetts Amherst where she was the keynote speaker for the 2014 Crossroads Conference hosted by the Comparative Literature Program. She spoke on refraction and topology as metaphors for understanding translation and we shared a fascinating conversation about the origin of the Japanese literary canon — did you know it was founded by women? Most striking however, at least for me, was that Professor Henitiuk hailed from Edmonton, Alberta — my home town! It was neat to see MacEwan University represented and nice to discover someone doing such fascinating work so near to my mom’s house. The next time I swung through town Professor Henitiuk and I met for coffee on campus. Her office is located in the rear corner of the Centre for the Advancement of Faculty Excellence, an inviting space which speaks to her energetic and progressive spirit. Many of her employees worked at standing desks built from pieces of Ikea furniture, the few doors present were open, and the space as a whole was brightly lit and abuzz. Our conversation covered Canadian politics, Alberta’s gradual leftward lean, the challenge of engaging community while working in academia, and what to check out when stopping over in Iceland. Professor Henitiuk was sharp, kind, generous with her insight, and damn good at telling stories. Hopefully a sliver of that comes through in the following interview.

Christopher Schafenacker: Your research ranges from addressing the political and cultural complexity of introducing 10th-century Japanese women’s writing to the West, feminist elements in magical realism, short story writing by women in India, and, more recently, issues involved with translating Inuit literature. The breadth of your work is startling. Where did it all begin? How did you first become interested in translation?

Valerie Henitiuk: Yes, my interests are broad, but there are and have always been common themes running through it all. Since my first MA (1989, in French literary translation), I have been keenly interested in women’s writing. My thesis at the time looked at a novel by Quebec author Louise-Maheux Forcier.

When I began studying Japanese literature, it wasn’t Japan per se that drew me, but rather the unique, surprising fact that the Japanese canon was created by women — Murasaki Shikibu, Sei Shônagon, Michitsuna’s mother… these 10th- and 11th-century authors, drawing on a female tradition that began even earlier (e.g. the 9th-century Ono no Komachi, ranked among the six great waka poets of Classical Japan), produced works in their native language by, for and about women, at a time when their male counterparts were trained to write instead in Chinese. Japanese was in fact known as “onna no de” or “woman’s hand,” an indication of how gendered the situation really was.

I met a professor at the University of Alberta, the great Classical Japanese scholar Sonja Arntzen, and was intrigued by the fact that she was translating a text (The Kagero Diary) that spoke in detail of a failing marriage, a woman’s struggle to raise her child with her estranged husband… it had been written in the year 926 but seemed so modern! So I set out to learn that language in order better to explore what had been written by these women. My first ever refereed journal article (“Translating Woman” in META 1999) was in fact a comparison of Sonja’s consciously feminist translation with the existing version by Edward Seidensticker, dating from the late 1950s.

My PhD being in Comparative Literature — rather than Translation Studies — allowed me more scope to continue to be eclectic and find my own connections among apparently dissimilar things — what David Damrosch calls “the like but unlike.”

After more than a decade working on Classical Japanese women’s writing, its translation and circulation in European languages, I felt last year a need for a fresh project. I happened upon a review of a new English translation of a woman-authored text described as “the first Inuit novel” and was brought up short. It had never occurred to me that Inuit had any literature to speak of, or that rather than going halfway around the world and a thousand years in the past, my next project could in fact arise from my own backyard!

“With Indigenous literature, the danger of appropriation of voice is particularly real and pressing. An Inuk friend and colleague noted just the other day how so frequently curiosity about her culture feels lacking in respect.”

Mitiarjuk[1] started writing Sanaaq in Inuktitut syllabics in the 1950s, when she at the age of 23 had just become literate, although it wasn’t published until 1984. Her work (more a collection of interlinked stories than a novel) has been translated into French by male, Sorbonne-trained anthropologist, Bernard Saladin d’Anglure (2002) and only very recently (2014) into English by his former MA student Peter Frost, also male. This piqued my interest (how could it not?!) in terms of the unexamined “man-handling” of a rare and unique text by an unschooled Inuk woman — the power differential is striking, and no one seemed to be addressing that point.

I’ve since realized there are in fact two “first Inuit novels,” the other being Angunasuttiup naukkutinga, or Harpoon of the Hunter, by Markoosie, originally published serially in 1969–70, and that almost all analysis of Inuit literature to date has been from an ethnographic viewpoint. There are few literary studies (the best book for learning about the Inuit literary tradition remains Robin McGrath’s 1984 Canadian Inuit Literature: The Development of a Tradition and no one has looked at this from a translation studies perspective at all. So, although I am only a beginner in Inuktitut, I decided to wade in…. My first two articles on the translation of Inuit literature are forthcoming in Target and Perspectives this fall.

CS: Often, you address topics far removed from the realm of your personal experience and even when working “in your backyard,” as you say, the texts you address arrive from a minority position that is not your own. How do you navigate the power differential that comes with this territory? Generally, how might translators and theoreticians intervene without intruding? Or can they?

VH: Yes, one of my concerns has long been the risk of being in a position of “speaking for.” With the Odishan short stories, I was approached by an Indian colleague, who is not only from Odisha, but also a specialist in the area, with many literary translations to her credit. So I was asked to contribute specifically on the Translation Studies side, also bringing not only a more general interest in women’s writing but also native English editing skills to the table. We’ve now done two editions of the collection, and so have developed a true partnership, where we each have specific defined roles.

“It is important to remain aware of one’s limitations in doing this kind of work, and humble about what one can accomplish. But the fact is that no one has done the work I’m now trying to do, and I think — I know — it’s important that someone do it.”

With Indigenous literature, the danger of appropriation of voice is particularly real and pressing. An Inuk friend and colleague noted just the other day how so frequently curiosity about her culture feels lacking in respect. And that’s partly what I’m writing about, about ethnographers treating Inuit as specimens rather than human beings, using Inuit cultural production to explain this or that pet theory without considering it as literature/art in its own right. About editors or translators assuming that an English version is close enough to the Inuktitut original that that original can safely be ignored. Where the Inuk author’s voice, perspective and lived experience are utterly absent from the paratext. So it’s a real problem.

As I write in the opening lines of a forthcoming article: “Translation from a ‘minor’ or peripheral language into a central, ‘major’ or heavily translated one (typically English, French or Spanish) cannot help but bear witness to an inherently unequal relationship, whereby minority cultures struggle to survive. While contact zones, famously defined by Mary Louise Pratt as ‘social spaces where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power, such as colonialism, slavery, or their aftermaths’ (1991, 34), may be unavoidable in today’s globalized world, they remain fraught with danger and opportunities for misinterpretation” (Pratt, Mary Louise. 1991. “Arts of the Contact Zone.” Profession. New York: MLA. 33–40). My article explores a striking translation choice in one relay translation of an Inuit text — a translation strategy that I take to be a metaphor for what often functions as that space of “miscomprehension, incomprehension” (Pratt 1991, 37) in which Inuit authors and non-Inuit readers may encounter one another. Although there is the risk that all I will do is add to that miscomprehension, my work strives to focus on “aspects of this project that one can at least begin to explore without more specialized knowledge, and which I hope that other scholars will then pick up and apply in more linguistically informed studies” of Inuit writing.

Again, the only way forward is to ensure that my own areas of inadequacy are acknowledged at the outset, and regularly — I don’t read Inuktitut yet, and in any case am not from the community. It is important to remain aware of one’s limitations in doing this kind of work, and humble about what one can accomplish. But the fact is that no one has done the work I’m now trying to do, and I think — I know — it’s important that someone do it. So my aim is really to start conversations. Ideally, someone with more Indigenous credibility and a more authentic voice will respond to what I say or write and chime in, moving the discourse forward, offering course corrects as and where needed. Hopefully we can even collaborate on subsequent stages of the project, if there is interest on their side in doing so.

It’s odd, as a scholar I am by nature a solitary creature. Working on my own and emerging from the cave only when I have a fully polished piece of work to present to others. But the kind of research I’m doing now has to be approached differently. I know that it absolutely needs a team approach, because there is so much I don’t know, or don’t have access to. And I find myself writing much more personally than I’d ever felt comfortable doing before, explaining the genesis of my project and telling of the journey I’m on, how I got to the point of writing a given article on a given topic. Referencing conversations that have helped me, challenged me, whether with an Inuk elder or a colleague in Linguistics. Revealing my feelings of vulnerability, and explicitly inviting other voices to join in.

“… Inuktitut is all about feelings, and that the process of adding affixes to a word (integral to the construction of Inuktitut sentences and phrases) is entirely to make something more understandable to the other person.”

To be successful, embedded in this kind of work must be the involvement of Indigenous individuals and communities as acknowledged experts of their own cultural production, thus closing the knowledge gap. I have become active with Inuit Edmontonmiut, a community group bringing together the over 1000 Inuit living in my city. I take private lessons with an Inuk elder, where the focus is less on grammatically dissecting the language, and more on how it functions in real life — which is taught through story and memories. This has been my approach so far.

CS: You speak of the collaborative approach required by your research on Inuk literature. Practically speaking, how does this work? Can you share specifics about how your writing process has changed while working in collaboration with members of the Inuk community as well as others with expertise beyond your own?

VH: First off, let’s just clear up some terminology. Inuit is, literally, “human beings” or perhaps “the human beings who are here” — its singular is Inuk (there is also a dual form, Inuuk). The language is known as Inuktitut, or the way of speaking of the humans. Inuit as a noun does not take either a definite or indefinite article, as this is implied in the Inuktitut word, so we might say, e.g.: “traditionally, Inuit lived a nomadic lifestyle.” Inuit is also the adjectival form: Inuit culture, Inuit literature, Inuit language. The word for non-Inuit (i.e. southerners) is qallunaat (singular: qallunaaq), which is usually glossed as “people with pampered eyebrows” or “heavy eyebrows,” although the etymology is unclear.

Inuktitut is in fact a very difficult language — much more challenging, it seems to me right now, than Classical Japanese! One of biggest hurdles is simply deciding which language to learn — across Canada alone there are 16 dialects, and these are not all mutually intelligible. Thankfully the two main texts I’m looking at were both written in the Nunavik (northern Quebec) dialect. Although standardization is a controversial topic, the writing system is for the most part relatively easy to learn. (Caveat: many texts lack any punctuation, as well as the diacritics that are essential to distinguishing between very different words.) Christian missionaries took a syllabic system (based on shorthand) originally developed by other missionaries for writing Cree, then Ojibwe, and tweaked it to suit Inuktitut. Sometimes this script is called an abugida — for each group of syllables (e.g. i, u, a; ki, ku, ka; ti, tu, ta), the same symbol is used, but rotated to indicate each of the three vowel sounds.

“… in today’s world, the internet is allowing the most remote communities to engage and share.”

A major part of the difficulty in learning Inuktitut is the lack of decent language-learning resources. There are few university courses (INALCO in Paris is said to graduate the most fluent speakers, but you need to commit to a 4-year programme). When I asked around for the best grammar textbook to help me study on my own, I was pointed to a book published back in 1978, by Lucien Schneider. Schneider was a great linguist, and widely respected for his mastery of Inuktitut, but his approach to the language is very out of date, and echoes his training as a priest: it is described entirely as if it were Latin — lots of tables full of noun declensions, etc. Of course, it doesn’t help that the copy I was able to obtain through interlibrary loan is badly mimeographed, and has faded to the point of illegibility in many places. My other source in learning Inuktitut is, as I’ve mentioned, weekly lessons with Inuk elder Mini Aodla Freeman (herself an author and translator; the second edition of Mini’s 1978 autobiography, Life Among the Qallunaat, recently won a Manitoba Book Award). Her approach is all about stories, establishing relationships, giving me some tools for a much more organic use of the language. I am expected to find the patterns on my own.

Very few non-Inuit achieve real fluency in Inuktitut, although I suppose it’s easy enough to learn enough to have very simple, everyday conversations. The aim for my own project is really exclusively about gaining literacy, so spoken Inuktitut is a lower priority. In any case, given all these challenges, I need constantly to be checking my understanding and assumptions with others, whether Mini, anthropologist Louis-Jacques Dorais (retired from Laval), or INALCO Inuktitut professor Marc-Antoine Mahieu, who have all been most generous with their time. The simplest questions tend to lead into the most complex correspondence.

To give just one example, let’s consider the Inuktitut for the English verb “to translate.” The entry in Schneider’s important bilingual Inuktitut-French dictionary suggests tukiliurpaa (“s/he translates”), and I asked Mini to help me understand the term. Unfamiliar with it in terms of “translation,” she commented that it meant instead “making understandable” or “explaining how things work.” Together we consulted Taamusi Qumaq’s unilingual Inuktitut dictionary, but the definition there for tukiliurtak refers to other things entirely. We came across another word that Mini said was related to translating, namely tukilik, “the understanding part” and, after some reflection, she suggested instead the word tusajik (literally “one whose habit it is to listen”), while cautioning that this was possibly a neologism.

What particularly struck me about this conversation was how the emphasis in Inuktitut seems to be very much about the effect of the translational act on the other person, i.e. its relational aspect, rather than more simply about words or their meaning, much less a “carrying across,” “setting over,” “turning,” “speaking after,” or any of the other metaphors in various languages with which hegemonic Translation Studies is more familiar. And when I suggested as much, Mini agreed. She further explained that Inuktitut is all about feelings, and that the process of adding affixes to a word (integral to the construction of Inuktitut sentences and phrases) is entirely to make something more understandable to the other person.

Qumaq’s dictionary is in fact full of definitions whose idiosyncrasy seems to challenge me to rethink everything. He defines uqara or “tongue” (which shares a radical with “speech”), for example, as follows: “My own thing, my tongue, it is inside my mouth, it has no bone, my tongue [is] my tool for telling something that makes sense” (Dorais, Louis-Jacques. 2010. The Language of the Inuit: Syntax, Semantics and Society in the Arctic. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. 262–63).

I next reached out to Dorais, whose book The Language of the Inuit: Syntax, Semantics and Society in the Arctic (2010) serves as an invaluable resource, and we engaged in a lengthy email exchange about this. Dorais concurred that tukiliurpaa has no connotation of translation, and went on to suggest the paired terms “qallunaatituurtisijuq, ‘(s)he makes it [the text] do [i.e. speak] like Qallunaat’” and “inuktituurtisijuq, ‘(s)he makes it do like Inuit’” (personal communication 2016). The equivalent for “making the text speak like Francophones” would be “uiguitituurtisijuq (‘makes it speak like the Oui-oui [people]’).”

The translator/interpreter training programme offered at Nunavut Arctic College, in Iqaluit, uses the term uqausiliriniq (‘the fact of dealing with words’), which can also refer to linguistics or language planning. But, noted Dorais, when inviting students to join the program, it is called tusaajiu[lauqsima]giaksaq, ‘what leads to being a tusaaji [i.e. interpreter’]’” (personal communication). As you may know, York University’s graduate students in translation produce a journal titled Tusaaji, which their webpage defines as “one who listens carefully [, …] who has an exceptional capacity to listen to others.”

Under Qumaq’s entry for tusaaji, he defines tukisititsiji as “one who makes [people speaking different languages] understand each other” (Qumaq 232; Dorais, personal communication). The basic signification of tuki (meaning) is “axis,” “one’s thoughts and words become meaningful when ordered along a specific axis.” Thus, in eastern Canadian Arctic dialects (other Inuit communities use different terms entirely), understanding literally means “encountering an axis,” or aligning one’s mind in the same direction as another’s and thus allowing one’s words to become meaningful, to make sense (Dorais, personal communication).

“Women academics … have perhaps taught me the most, by grounding their work in the very real context of post-secondary education and how they themselves have navigated its pitfalls. And in many cases with such grace and strength!”

CS: Earlier you point out that no one is doing the work you have undertaken and, though you may be an outsider, it is important that a conversation begin around Inuit literature. Why has this literature been neglected? Canada has a rich history of publishing in translation and is home to many of the world’s leading translation theorists. Why hasn’t Indigenous writing played a more prominent role in national discourses?

VH: The answer here is not so straightforward. Inuit culture is traditionally an oral culture (literacy arrived in most Canadian Inuit communities only around the turn of the 20th century), so the existing literary corpus is small. [2] Although there is in fact a great deal of work to do on the more ephemeral journals and newsletters published in the North, many rather shortlived, which have published a range of work and authors. And, in today’s world, the internet is allowing the most remote communities to engage and share — I am fascinated, for example, by the work of Rachel Qitsualik, who writes in both Inuktitut and English. She is a prize-winning author of children’s literature, but also has brilliant short essays published online. Younger Inuit are prolific in the fields of rap music, etc., although I may be of the wrong generation to study that in any depth!

Greenland has a very different history, by the way, and a more extensive network of authors. Of great interest to me is the powerful impact on the early development of literature in Kallalisut owing at least in part to the Danish government’s decision to ensure European literature was translated and available for Greenlandic Inuit to read. Even until the 1960s Canadian Inuit were likely to encounter only Bibles and hymn books translated into Inuktitut, and there remains very little literary translation activity into the language.

Literary analysis of Inuit cultural production really got underway only in the 1980s, and even then was still dominated by more ethnographic approaches. Robin McGrath is the pioneering figure in Canadian Inuit literary studies, but a younger generation including Keavy Martin has taken up the reins, bringing an approach grounded in the work of J. Edward Chamberlin, Robert Allen Warrior, and others. They are also drawing from the better established field of Indigneous literary study more broadly. Canada has a great number of brilliant writers, ranging from Thomas King to Thomson Highway to Lee Maracle to Joseph Bydon, Eden Robinson, Richard Wagamese…. But it’s only recently that such writers are really becoming central to conversations around Canadian literature, rather than being ghettoized. More attention is being paid to this literature, in all its complexity, and publishers (as well as prize adjudicators) are responding. Of course, the specific context politically and socially, in a post-Truth and Reconciliation Canada, is playing a large part in public interest.

CS: You have mentioned a number of mentors in our conversation, including Classical Japanese scholar Sonja Arntzen, Inuk elder Mini Aodla Freeman, and others. Can you speak more generally about mentorship? Who have been your greatest influences? Who most shapes the trajectory of your work?

VH: Mentors are vital, even if sometimes their value to one’s development is fully appreciated only in hindsight. It is by looking back at my career that I see how much impact various colleagues and friends have had on not only what I’ve been able to achieve, but also on the very questions I have felt able to ask. One of my great advisors in the decade following my PhD was of course David Damrosch, who guided my postdoctoral work at Columbia and then welcomed me as a visiting scholar during my sabbatical at Harvard. David is a generous scholar, encouraging of students and junior colleagues, and it may well be that I took his own wide-ranging work (as a student he studied Egyptian hieroglyphics) as a sort of permission for some of my own more esoteric research tangents! He is also very interested in questions of translation as they relate to his own specialization in world literature.

Women academics, though, have perhaps taught me the most, by grounding their work in the very real context of post-secondary education and how they themselves have navigated its pitfalls. And in many cases with such grace and strength! I was privileged to be supervised by the Iranian scholar Nasrin Rahimieh as well as the incomparable Isobel Grundy (whose Orlando Project is so important), to name just two — I couldn’t even begin to list all those to whom I’m grateful for countless opportunities to learn and to grow.

CS: One last set of questions to conclude our interview: First, what new frontiers might Translation Studies broach? Is there territory within the discipline that remains insufficiently explored? Are there silences yet to be filled? And second, on a related note, who needs wider representation in translation? Specifically, which writers, texts, communities, or literary movements go under-translated or not translated at all?

VH: As you know, I edit the journal Translation Studies for Routledge. Our editorial team regularly discusses the need to diversify the content we publish, in terms of topics, languages, cultures, geographic regions represented. In each issue, we certainly seek to include work by colleagues affiliated with universities outside the UK and North America — given that this is where our team is based, we are well aware of the danger of simply reproducing what we already know. We are very keen to publish work by scholars in parts of the world that rarely have a voice in our discipline. But it’s not that easy. Scholarly traditions differ. Not all potential contributors have the grounding in our discipline that we need to see, even in more interdisciplinary pieces. Young scholars need time to develop. Further, we publish exclusively in English, so where the potential contributor has a different mother tongue, that can be another barrier. Our resources are limited, and sometimes we just can’t accept a piece, no matter how interesting, that is going to require hours and hours of editorial work.

This doesn’t mean we just give up, but it is a challenge. Where possible, in declining a contribution, we give constructive feedback on the kind of work we need to see. Carol O’Sullivan and I recently published a book chapter titled “Aims and Scope” with the very specific goal of providing scholars outside of Europe and North America (the book grew out of a Translation Studies conference in China) with specific information on how to write for a Western journal, and what the occasionally painful process of copyediting involves. Of course, the information would prove helpful as well for many located in the West, especially younger scholars just starting their careers!

Clearly, I have a personal interest in seeing more work done around translation relating to First Nations and Inuit in Canada. But minority languages and cultures around the world are calling out for more of a platform, so that’s one way our discipline of Translation Studies can be enriched by difference.

It’s also fun when a submission arrives that addresses something happening in the world right now. TV, film, new technologies, changing world order…. Our journal has recently published on both Arabic Hip Hop and the use of Arabic graffiti in the TV series Homeland. And sometimes I await that one article that never comes — for example, I was so looking forward to receiving a submission on that fake sign-language interpreter at Mandela’s funeral — such a rich vein to be mined!

As I write this, it is August 2016 — the third annual Women in Translation month (https://pen.org/blog/women-translation-month-moving-toward-parity). Now, that’s a wonderful initiative! Helping readers focus on women writers, women translators, women readers and scholars of translation…. Maybe we could use similar initiatives for other voices that deserve to be heard and appreciated. Opening up to such diversity can’t help but enrich our lives as well as our discipline, allowing the many, many silences that exist all around us to begin to be filled.

CS: Thank you!

[1] The author’s full name is Salome Mitiarjuk Attasi Nappaaluk, but it should be noted that naming is a highly contentious topic in (post)colonial Inuit culture. Traditionally, Inuit men and women used a single non-gender-specific name, and were often referred to by terms establishing kinship. Missionaries began baptizing Canada’s Inuit as early as the eighteenth century. In the 1940s, the government assigned each Inuit a number, issuing identification disks not unlike dog tags; then, in the 1960s, Inuit were forced to adopt surnames, often those of their fathers or grandfathers. Addressing this particular history as well as other forms of colonial abuse occurring through the establishment of the nation-wide residential school system for Indigenous children, the 2015 report of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission calls upon federal, provincial and territorial governments to facilitate the process whereby residential school survivors may reclaim names forcibly changed.

[2] While finalizing this interview, we noted the passing of publisher Mel Hurtig. In the 1970s and 80s, Hurtig Books was responsible for publishing a great deal of Inuit literature in English, including Paper Stays Put (Gedalof and Ipellie), Tales from the Igloo (Metayer and Nanogak), Stories from Pangnirtung (illustrated by Arnaktauyok), and People from Our Side(Pitseolak).

Originally posted August 26, 2016 on https://medium.com/drunken-boat by Christopher Schafenacker.

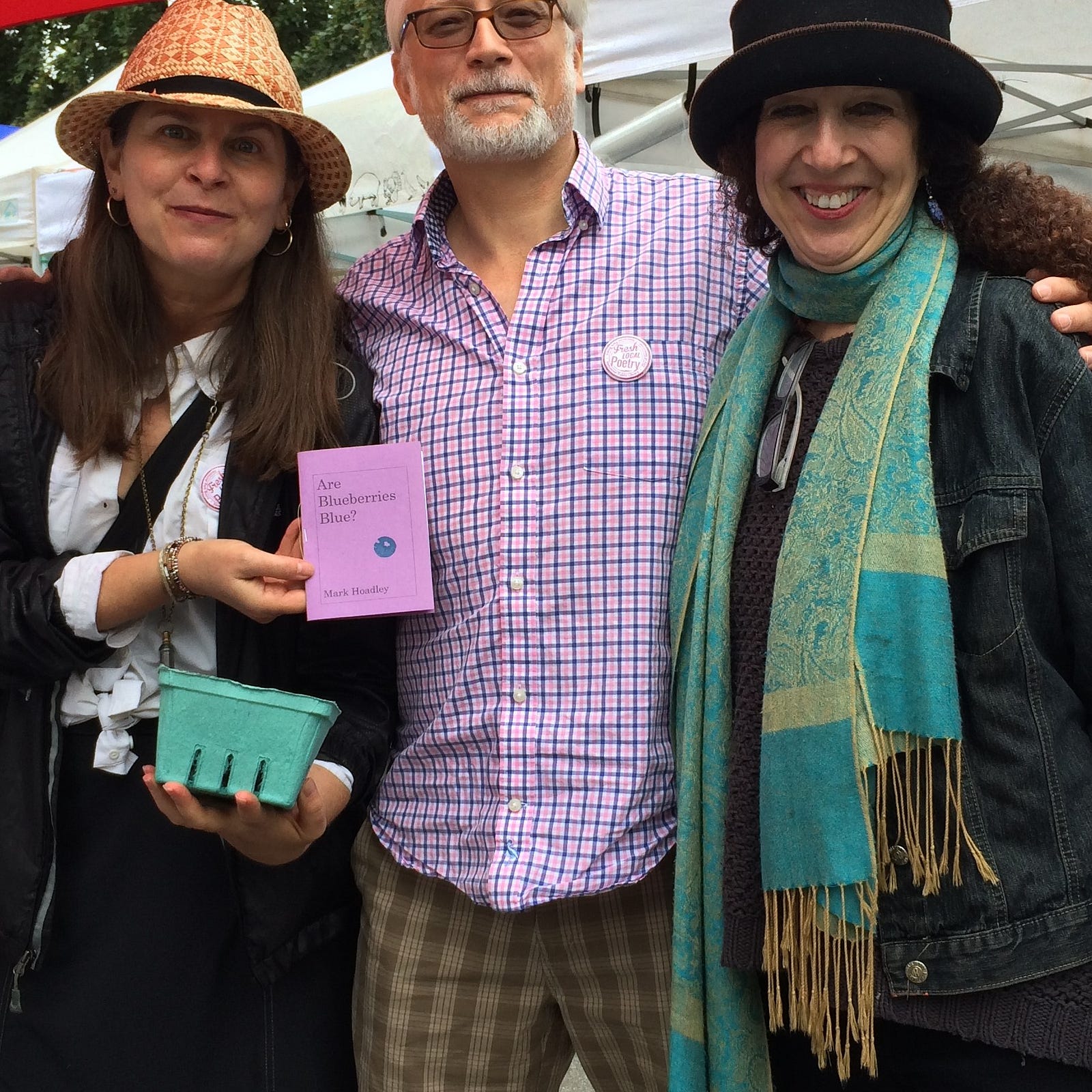

image: Jay Banks

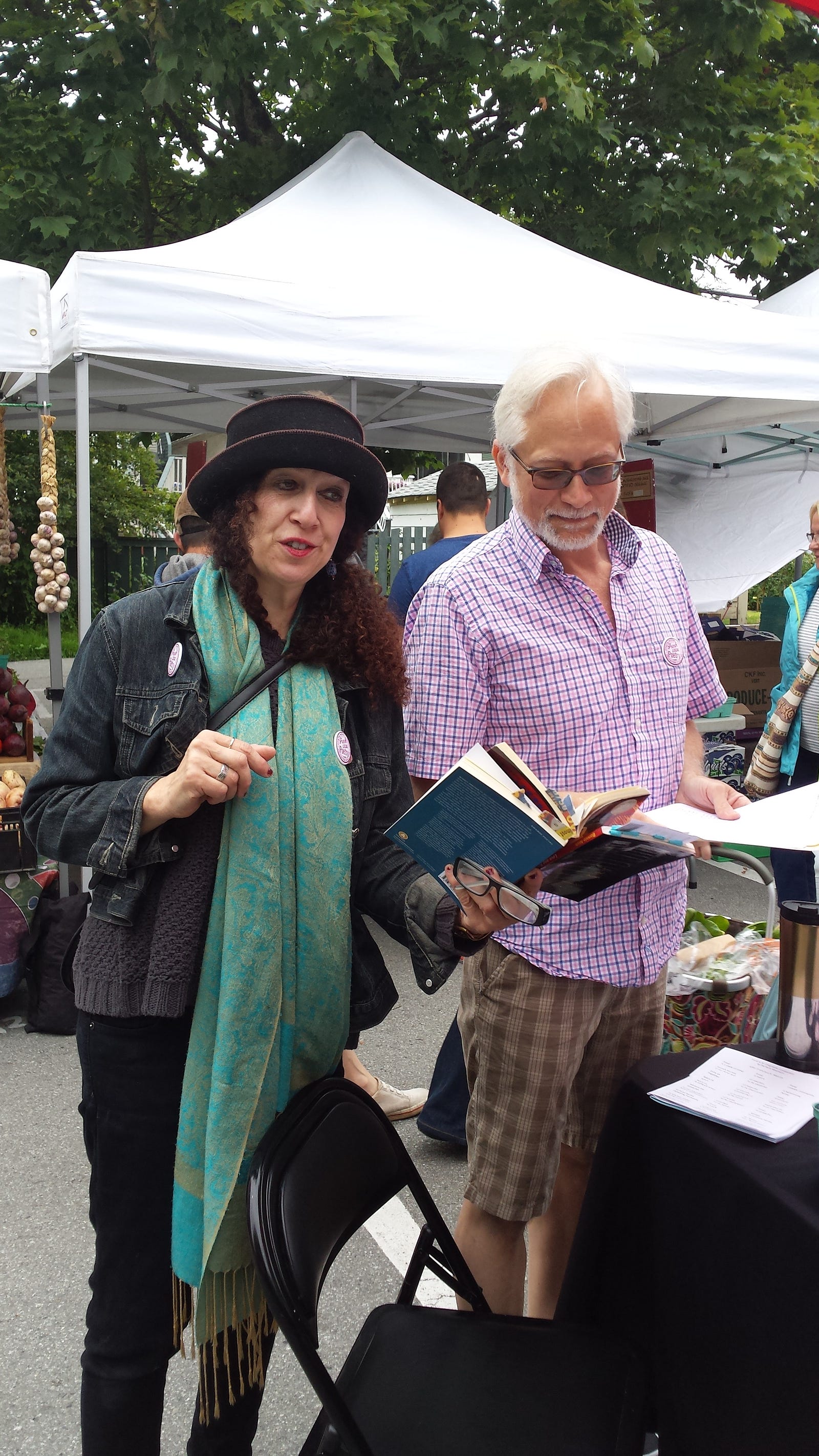

image: Jay Banks