THE DEAF POETS SOCIETY MANIFESTO

Here to Right Literature

Disability is the civil rights movement you’ve never heard of. That movement is the reason you can reliably find curb cuts in the sidewalk and elevators at the mall, for your strollers, for your bicycles, for your tired, tired feet. The bathroom stall in the airport large enough for your oversized suitcase and a sun salutation or two? The captions for the TV show you’re binge-watching on mute so your boss doesn’t hear over your cubicle wall? You’re welcome.

Disability rights affect everyone, disabled and able-bodied alike. These rights envision a free and appropriate public education for all children. The right to not have to crawl up courthouse steps in Tennessee. To not lose your job after chemo. De-institutionalization.

The vision of disability rights began in legislation, which resulted from significant advocacy and input on the part of people with disabilities and their allies. These laws — the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the landmark Americans with Disabilities Act — articulate a vision at the level of society. These laws reflect a progressive vision aimed at reorienting and reorganizing and equalizing something huge, complex, and moving: for us, that motion was pushing against us. These laws righted a skewed trajectory. But we’ll leave law to the lawyers. We’re here to right literature.

2.

Against Invisibility

Here at The Deaf Poets Society we are not all d/Deaf, and we’re not all poets. Some of us are sick as fuck; some of us used to be, which is to say, will always be, which is to say what Audre Lorde — patron saint of black queer sickness — already said in The Cancer Journals: “Once I accept the existence of dying as a life process, who can ever have power over me again?” Lorde’s question is concerned with power and who wields it, with the story of the body and who tells it. We believe that the actual literature and art of people with disabilities and chronic illnesses cannot be constrained by the binary of life and death, or of doctor and patient, of temporarily able-bodied and weak, pitiful Other.

O dead white male able-bodied poets, O interviewers who ask us “If you had just one wish…”, O well-meaning friends and family and neighbors and lovers who assume that an absence of illness or disability is wholly synonymous with health: We have tired of your presence in our stories, poems, and art. We are not your dystopia, your travesty, your nightmare, your wet dream, your fantasy, your paradise. Don’t pray over us. Whatever prayers we seek will not be yours, and whatever we have to mourn, we will mourn it ourselves.

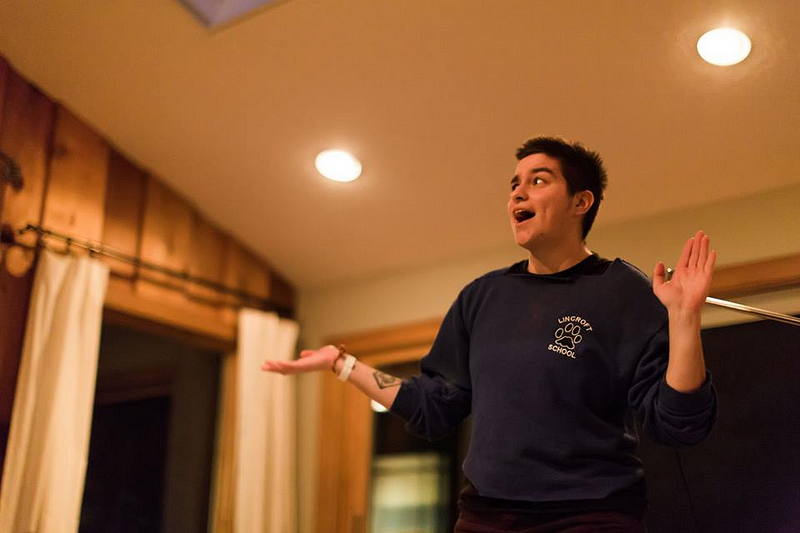

At The Deaf Poets Society, we aim to create a literature of a society with a different center, where the writer with a disability is not literally seated on the floor of the writing workshop while others are seated at the seminar table, where the writer with a disability does not spend years telling stories that make others comfortable, and themselves invisible. ‘Deaf poets’, as a descriptor, is as good as any. ‘Deaf poets’ understand what people with disabilities also understand, what Deaf poet (and Issue 1 contributor) Raymond Luczak means when he talks about orphans.

What we aim to incubate and amplify here is the literature of the movement that fights back against bigoted policies of sterilization and the racist, classist pseudoscience of eugenics. This literature fights the echoes of “three generations of imbeciles is enough” in the mocking of a physically disabled reporter by the presumptive Republican nominee for president.

We are the literature of the Martha’s Vineyard of the 1700s, where everyone on the island knew sign language, of the energized Gallaudet University students and alumni who shut down a campus to demand a Deaf President, and then, a generation later, protested again for a Deaf President who matched their diversity in race and culture. We are the literature of the movement that passed laws requiring all phone calls to work for all people and everything on the internet to work for all people — from the audio of the cat video your mother posted to Facebook to a JAWS-narrated description of a photograph of Mars. We are that literature on the internet, and the aim is always to be accessible to every reader. We are the literature of a people who understands the difficulty of managing physical pain. Of a people who spend days in the white rooms of hospitals, in the labyrinth of referrals and insurance company touchscreen menus that would dizzy Kafka. We are the literature of the recovery rooms, the psych ward, the hospice.

3.

This is a here for us to find us

Since we’re not in the canon, we began TDPS as a here, a here for you to find us. Or, more to the point: this is a here for us to find us. What does that mean in a practical sense? It means that the poetry, prose, art, and reviews we publish will be composed by people with disabilities, period. The benefit of this might seem obvious, but it’s worth saying them clearly: the existence of a platform will provide the opportunities that are harder to access elsewhere.

Because the voices of all the writers will be the voices of people with some disability or other, the collective voice will, in our ideal, showcase the wide spectrum of people who identify as having a disability. For our community, diversity involves a huge range of disabilities. In our community, diversity also involves a huge range of other facets of identity.

Incubating and amplifying the voices of writers, poets, and artists who are Black, indigenous, people of color (BIPOC), queer, immigrant, working-class, women, or other people relegated to the margins of literature is a crucial part of our work. Our work must also create a space where writers with disabilities who are white will recognize their own complicity in white supremacist systems. Such systems have advantaged white people, including those with disabilities. The work of white writers with disabilities in our magazine needs to reflect an understanding of that historical injustice and, in the slant way that art can, consciously work to dismantle it going forward.

Beyond publishing and reviewing the work of underrepresented folks, allying with existing fights for social justice is essential. A disability-focused literary magazine can find ways to fight anti-Black racism and police violence, even in our small way. If we can do this often enough and effectively enough, disability can be centralized in discussions about social justice activism, rather than an afterthought. We will mirror the progress of the last half-century, with our concerns, our ideas, our words, our art, our stories, integrated into communities. We will help create access where there had been a barrier, language where there had been a void.

4.

No, We Have Not Met Before.

You may think you’ve met us in literature, in “Good Country People,” in The Miracle Worker, in “Idiots First.” Every damn Christmas you hear the pitiful rattle from Tiny Tim’s chest. At a barbecue your neighbor’s precocious middle schooler recounts to you the plot of The Fault in Our Stars, and you might think, “How tragic.” In an air-conditioned theater, you see a preview for Me Before You, you might think, “How sad.” Yes, sad, yes, tragic, but hardly for the reason you may think. You may think you’ve met us — people with disabilities — here, in the cliched first-thought, worst-thoughts that comprise too much of the imagined work from many an able-bodied brain. Here’s the truth: We’re not there. We have always been here, living boldly, in front of your able eyes, within your able earshot, just within your able reach.

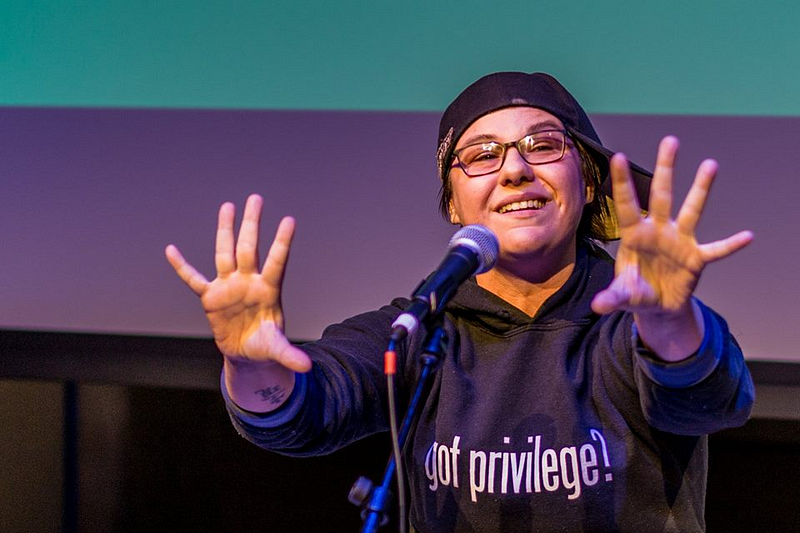

Here at The Deaf Poets Society, all bodies are welcome at the table, with disabled artists and writers at center stage. If you are abled, come sit and listen to the voices and visions of Black, Asian, Arab, indigenous, Jewish individuals across the disability spectrum and across gender and LGBTQIA status. Understand that our work resists closure, resists bilateral ideology about disabled and abled bodies, resists simple delineation of complex bodies and lives. Understand that, if you’re a cisgendered, heterosexual, white person with a disability, you do benefit from privilege in a way that a person of color does not, and it is you who will determine whether the privileges bestowed on you via white supremacy, transphobia, and homophobia diminish the voices of your counterparts. Allies are key to systemic change and true disability justice; as long as someone is not free, nobody is free.

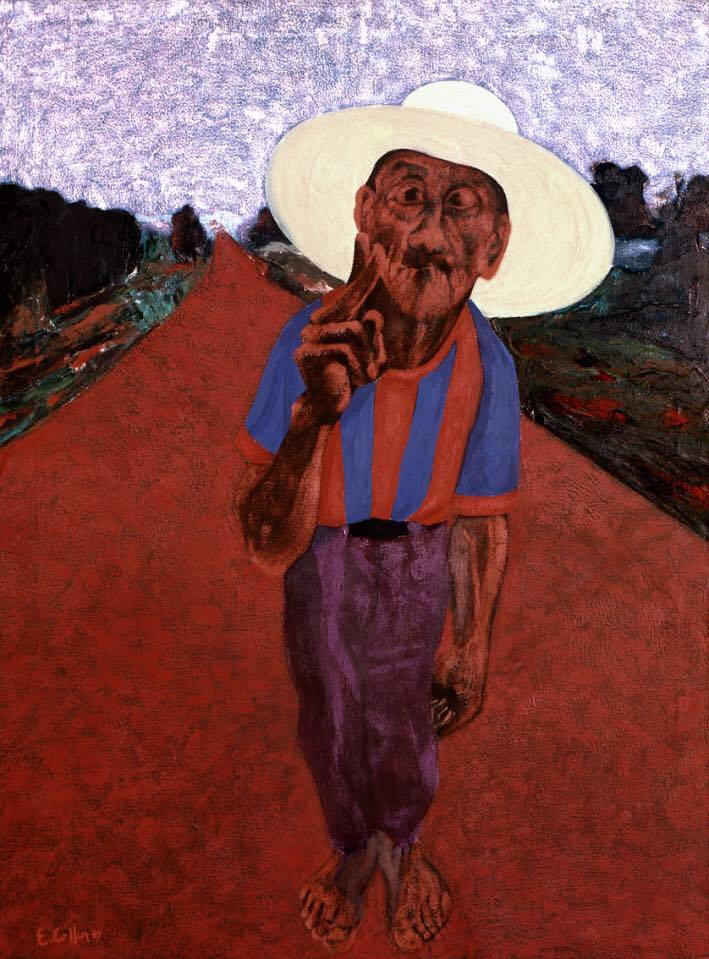

So come to our home, come in and sit. Marvel at how our work reveals the wide spectrum of experience across identities and at the intersections. Marvel at how alive we are, despite constant and implicit and complicit metaphorical arguments to the contrary. Marvel at how our language muscles through the page with verve and idiosyncrasy, at how our brushstrokes and pencil markings and photographs undo what you think you know about the body, what the narrow range of voices in the traditional canon thinks they have figured out, but never did and never will.

Originally posted June 29, 2016 on https://medium.com/drunken-boat by The Deaf Poets Society.